Withdrawal 1922–1923

Due to the isolationist foreign policy of President Harding (1865–1923) combined with improved German-American relations, support for a continued occupation dwindled among American politicians and public opinion.

In March 1922, the American government decided to withdraw all of its troops from the Rhineland by July 1, 1922, although General Allen believed that this decision came too early. After some discussions within the U.S. government, the decision was revoked in June 1922. The American troops were to remain with a reduced force of only some 1,200 men in the Rhineland.

The French had always attempted to gain influence in Koblenz, which Allen and Pershing had managed to prevent until that point. Having only some 1,200 American soldiers left, however, Allen was forced to accept the stationing of additional French troops in the American Zone to ensure public order and control. However, the French units were put under Allen’s command.

The end of the American Forces’ presence in Germany on the Rhine came with the occupation of the Ruhr: Despite all the warnings from the British and the American government, French and Belgian forces invaded the German Ruhr area on January 11, 1923. As a result, the American government decided to end its Rhineland occupation. General Allen received orders to bring home all remaining Doughboys.

At Ehrenbreitstein Fortress, the Stars and Stripes were lowered. Three days later, the French officially took control of the American occupation zone. They quickly demonstrated their unquestionable authority to the Germans, making the life of the locals much more difficult.

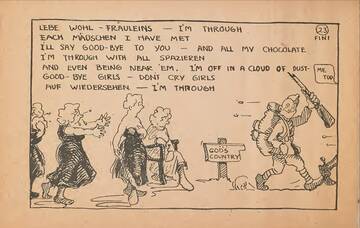

For many Germans, this constituted a significant change to their daily lives. The Doughboys, who had only recently accustomed themselves to the region, now had to go back home. Reichskommissar Hermann von Hatzfeldt-Wildenburg (1867–1941) met General Allen a last time during the farewell ceremonies. He said to Allen that the beginning of a political friendship between Germany and America had been made. The Americans had arrived as enemies, but they departed in friendship, hoping that the Germans would continue to respect humanity and a sense of justice. In retrospect, he was right, as the short period between 1918 and 1923 represented in part the model for the character of the future American Occupation of Germany after World War II.